I think most of us divide our emotional experience roughly into two categories.

The first category is feelings/emotions/moods that we want to have such as happiness, excitement, joy, curiousity, love.

The second category is feelings/emotions/moods that we don’t really want to have such as anger, sadness, stress and anxiety.

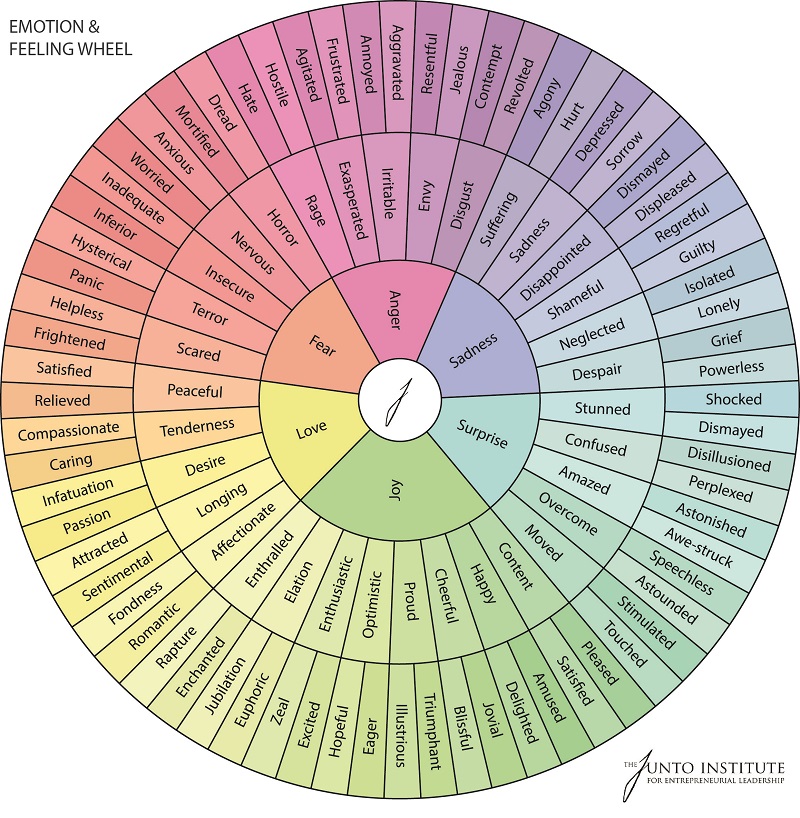

To illustrate this, check out the following emotion/feeling chart and quickly identify those feelings you want more of in your life, and those you would happily take less of.

Despite us categorising feelings/emotions in this dualistic way, all emotional experiences are important sources of information for us to use.

Sometimes however we misinterpret what these feelings/emotions are trying to tell us.

Take stress and anxiety for example. From the perspective of how we experience them, we typically assume that their presence means:

- Something is going wrong

- Something is about to go wrong

- We’re broken or damaged

- I’m in a dangerous situation

- I’m at risk

Oftentimes this is correct, but you need to pay attention to the context in which they are occurring to make full sense of them.

For example, if you are experiencing stress or anxiety because of bullying or victimisation, then the interpretation of being in a dangerous or risky situation is likely correct. Likewise if you are being chased by a large bear.

But if you are experiencing stress or anxiety in the context of your studies, then you may need to dig a little deeper to understand what those feelings/emotions are trying to tell you.

Your brain is trying to tell you something

When confronted with something like study and exams, your brain does a rough calculation comparing demands (how difficult the work is) and resources (your abilities, time).

If resources > demands, then generally your stress levels will be lower as you have the ability to meet the demands of your studies.

However if demands > resources, your brain and body initiate a stress response.

Now often we interpret that stress response in the same way as we might if confronted with a large angry bear – namely to flee the situation. In the case of study and exams this would mean avoiding both (procrastination).

But actually, the body initiated that response in order to give you the arousal and urgency required to modify the equation somehow by either:

- decreasing the demands (e.g. delving into the work more so you understand it better)

- increasing the resources (e.g. allocating time and attention to addressing the demands, modifying your study strategies)

And you can harness that energy and urgency by changing how you label and describe the stress response in your head.

If you think I am talking out my arse, then I direct you to a 2016 study by Jameison, Peters, Greenwood and Altose from Social Psychological and Personality Science.

They randomly assigned math students undergoing exams as part of a math topic, to one of two pre-exam interventions.

The first group were taught that stress arousal is an adaptive coping response that can aid performance. We know this is the case because one aspect of the stress response can be changes to cardiac efficiency and vasodilation, which increases blood flow to the brain and improves performance. Evolution gave us this mechanism in order to assist us in responding to acutely stressful situation.

The second group were told that stress should just be ignored and that was the best way to deal with it.

They found that students allocated to the first group perceived the exam situation differently (i.e. resources more closely matched to demands), had improved exam performance, and actually had marginally better final grades at the end of the topic.

All this from just a simple piece of information about the stress response!

Implications

Study and exam situations are stressful but necessary. In this context it is important for you to realise that stress is not necessarily harmful for performance and actually can be harnessed for improved performance – stress can be a resource.

Key to this is how you interpret and label the stress and its impact on you.

The take-home message from this work (and other similar work) is to remind yourself of the adaptive functions of stress when confronted with stressful study situations – starting an assignment, sitting an exam, doing a presentation. Focus on these adaptive functions instead of either trying to ignore the stress, or dampen it down. I won’t go so far as to say that the ‘stress is a gift’ but it is there, in this situation, to help you modify the demands>resources equation.

This simple reminder can help you harness the energy and urgency that comes with the bodily stress response.

Want more on how to harness stress?